US still makes billions in China chip sales, and it's all at risk

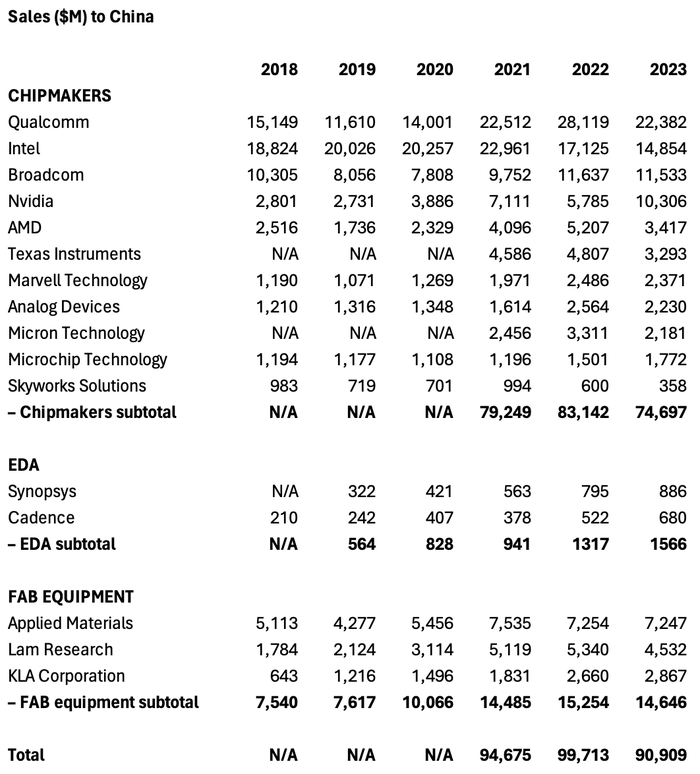

A full embargo on US chip sales to China would deplete sales at 11 US chipmakers by nearly $75 billion, more than a quarter of their combined revenues.

A filing with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is a company visit to the confessional when it exposes itself to the scrutiny and judgement of the regulator. Recent disclosures reveal some impious truths about chip companies and China. First, that sales by certain US majors to China last year exceeded levels in 2020 by nearly $22 billion. Second, that Qualcomm, a giant in smartphone chips, continued serving Huawei, a Chinese Beelzebub to the strictest US critics. Third, that western chipmakers will do all they can to keep serving Chinese companies, Huawei included.

This is sinful behavior to the anti-China cohorts. Sanctions introduced under Donald Trump, the former US president taking another run at the White House, and strengthened by Joe Biden, the incumbent, are supposed to limit China's access to US chip technologies. But companies that have grown fat off of China sales have sought loopholes and pushed for exemptions. They have been able to secure them, too.

Qualcomm, notably, picked up a license to sell 4G chips to Huawei in the final days of the Trump administration, according to a reliable source. It has acknowledged its dealings with the Chinese vendor in reports filed with the SEC, warning investors that a 5G revival at Huawei could hurt its China business. Overall shipments to China dropped by $5.7 billion last year, to about $22.4 billion. But they still exceeded sales in 2020 by some $8.4 billion.

Intel still on the inside

The latest bust-up concerns Intel. Much like Qualcomm, it previously managed to evade a full ban on selling to Huawei and has continued to supply chips for Huawei's line-up of personal computers. Despite this, there was apparent shock and outrage when Huawei last week showed off a new laptop – the MateBook X Pro – powered by an Intel chip. A marketing reference to artificial intelligence (AI) seemed to provoke this reaction: US lawmakers seem to think any chip even mentioned in the same breath as AI – whatever AI actually means – should be off-limits to China under existing rules.

Unlike Qualcomm, Intel includes no commentary about Huawei in its latest SEC filing. This did, however, show it generated nearly $15 billion from chip shipments to China last year. And while this was $8.1 billion less than Intel made in 2021, it still represents about 27% of total sales in a year when those total sales dropped 14% because of wider economic and market-share issues.

Judging by their various statements to the mainstream press, US Republican hawks seem perplexed by the Department of Commerce's apparent leniency and unwillingness to impose a full embargo on China. Yet this would conceivably devastate US commercial interests more than it would hinder a China determined – in any case – to be technologically self-sufficient.

Analysis of numbers is complicated because organizations report in different ways. Qualcomm's China sales, for instance, cover all shipments to China, even if the customer is South Korean and the chip eventually powers a device sold in Europe. Both Texas Instruments and Micron Technology now count sales under China only if the customer has its headquarters there. The convention is unclear for some companies.

(Note: results are for full fiscal years nearest to calendar years shown. Source: companies)

Nevertheless, based on headline China figures, a full embargo would deplete sales at 11 big US chipmakers by about $74.7 billion, a figure equal to about 27% of their combined revenues. Such a massive drop would probably have repercussions for US jobs as well as research-and-development spending on chip technology – all while China pushes for self-sufficiency and weighs punishments of its own.

These could include restrictions on US access to semiconductor raw materials concentrated in China. Meanwhile, China seems to be figuring out that measures introduced by US authorities as sanctions against China could do more harm to US companies. Ironically, this could put the latest Chinese policy moves in complete alignment with the wishes of US hawks, if a story published in The Wall Street Journal last week is accurate.

According to that story, Chinese policymakers seem to agree with some US Republicans that Chinese companies should not be allowed to buy US chips. China Mobile and China Telecom, two of China's big three telcos, have reportedly been ordered to phase out all foreign processors by 2027.

This would follow a Chinese decision last May to ban Micron Technology, a US maker of memory chips, from certain critical infrastructure projects. Despite signs of a subsequent rapprochement, Micron's China revenues fell by a third last year, to less than $2.2 billion. In July 2023, China also announced restrictions on exports of gallium and germanium, two raw materials used in semiconductors. In the radio access network market, Huawei's proficiency in power amplifiers – where it claims to be a generation ahead of rivals – has been attributed partly to its investments in technology designed around gallium nitride rather than silicon.

Pursuing Huawei licenses

US chipmakers also appear to have actively resisted sanctions, including US efforts to cut off Huawei. Broadcom made $11.5 billion in China sales last year, up from just $7.8 billion in 2020. But it evidently hopes the loss of Huawei as a customer will be temporary. US export restrictions, it said, have "required us to suspend sales to Huawei until we obtain licenses from the US Department of Commerce. We may be unable to obtain or maintain the necessary licenses to allow us to export products to them," it adds, before describing government actions as "restrictive."

As shocking as this may seem to critics, US policymakers may be even more horrified by figures that show sales of chipmaking equipment and software to China remain high, despite efforts to restrict access. Such tools and knowhow effectively help China to produce its own chips instead of buying them from US companies.

Cadence and Synopsys, two US developers of electronic design automation software, made nearly $1.6 billion in China sales last year, up from $1.3 billion in 2022 and just $828 million in 2020. Sales to China of fab equipment by Applied Materials, Lam Research and KLA came to $14.6 billion in 2023. That was down from $15.3 billion in 2022, but a substantial increase on the $10.1 billion they made in 2020.

Worst of all, though, is ASML – not a US company but a Dutch one. It is the world's dominant player in ultraviolet lithography, a technique for imprinting chip patterns on silicon wafers, and an acknowledged monopolist in extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV), the latest generation supposedly needed to produce the most advanced chips. Under export controls in the Wassenaar Arrangement, the Dutch government forbids EUV sales to China. But Chinese companies have been able to obtain a slightly older technology from ASML called deep ultraviolet lithography (DUV). By pushing DUV to its limits, SMIC, a Chinese foundry, was seemingly able to produce advanced 7-nanometer chips.

The financial evidence is plain in ASML's latest annual report. After making sales of €2.7 billion (US$2.9 billion) in China during 2021, and €2.9 billion ($3.1 billion) in 2022, ASML generated a whopping €7.3 billion ($7.8 billion) there last year as companies like SMIC snapped up DUV equipment before loopholes were closed. Teardowns of new Huawei smartphones have exposed 7-nanometer chips from SMIC's stable. And ASML's fingerprints seem to be all over them.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)